I was delighted to be able to interview John Logan, Programme Director and Head Counsellor at the Edge rehab centre in Thailand, about their gaming addiction treatment programme. This programme has been only been running for a year (as I write in May 2019) and is a trailblazer in the treatment of this very 21st century condition.

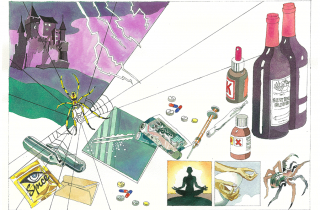

Prior to setting up this programme, the professionals at The Edge rehab were finding that many of their clients were cross-addicting into gaming. And it was not uncommon for gaming addiction to be connected with cannabis use.

The Edge programme is gender-specific – for guys. 90% of gamers are young men.

The defining feature of the programme – as with all programmes at The Edge – is that it’s holistic, and every single part of it is experiential.

What does “experiential” means in this context? I know it’s a word that we all think we know the meaning of, but could you define it in terms of what it means for clients at The Edge rehab?

Because young men find it difficult to access and verbalise their feelings, experiential therapy is a non-traditional therapy that focuses on the feelings that arise in the here and now as a result of the experience. For example, a client who becomes frustrated at his inability to run or cycle as fast as his peers.

And you partnered up with Cam Adair of GameQuitters to devise this specialist programme?

Yes. We’d already devised a programme dealing with the addiction side, as we understand addiction. Cam understands gaming addiction. This has given us the ability to fashion a programme for gamers that’s highly specific.

What is your view on addiction? Do you see it as an illness?

It’s a brain disease in which the brain’s reward system – i.e. dopamine – isn’t working. We believe the best natural way to get the dopamine system working again is through physical exercise. So we major on physical activity.

Why do you think it’s the case that it’s predominantly males who become addicted to video gaming?

It’s because men tend to be more goal-oriented; they think in terms of going from one ‘straight line’ to another. Rewards (which you get at each level in a game) mean progress to them.

Girls tend to be addicted to Instagram, Snapchat etc. So they are screen addicts, rather than gaming addicts. Women are more interested in chatting.

You can see the difference between men and women in their approach to problem-solving. When faced with a problem, guys want to go straight for a solution. Women want to talk about the problem first.

What would you say to parents of the 10% of gaming addicts who happen to be girls? Where can they go for help?

I recommend they join GameQuitters.com.

How do you overcome the fact that men don’t like to talk about their feelings?

As mentioned earlier, our programme is based on experiential therapy. So for instance, when the guys start doing some Thai boxing, they’re pushed outside their comfort zone and then they talk about that experience in group. They talk about the difficulties they experience with the sports they’re required to participate in. One client who was training for the triathlon was refusing to do the running section. He told the group that he was terrified of being last. This was then something that could be explored and processed in the group sessions and they came to the answer together that it’s OK to say:”I’m afraid of being laughed at”.

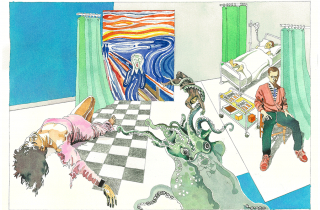

What state are gaming addicts in when they come to The Edge for treatment?

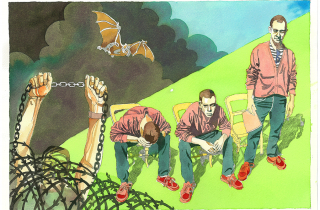

When clients enter our gaming addiction programme, their primary relationship is with the game. They have no real human interaction and so when they do have to talk to people, they get social anxiety. Quite a few of our clients have been bullied in school; in their gaming, they have been able to ‘live’ through avatars, and they create a whole different personality.

We notice with gamers that about 90% of them complain of anxiety and depression. It’s a chicken and egg situation really, because drugs and gaming are causing the anxiety just as much as they’re being used to self-medicate it.

So how is your programme ‘gamer-centric’?

Through our partnership with Cam Adair, we understand where gamers are coming from. We try to get behind their motivation. It’s a question of how to take that motivation or mindset and bring it into real life. So we’ve built rewards into the programme, with measurable growth. We do this by fitness programmes through gym and triathlon training.

This focus on physical activity is also the best thing for beating the depression that gaming addicts suffer from.

We specifically address the gaming addiction though a 42-day digital detox. The clients have no access to any electronics during this time.

There’s a crucial difference in approach between treating gaming addiction and other addictions. Total abstinence is the foundation of treating substance addictions. But you cannot insist that people never use a computer again – because computers are necessary in their professional lives.

So an important part of the programme is the re-integration of technology through mindful and purposeful use. We begin with three 15-minute sessions per week, and each session is preceded by meditation. They are allowed only one screen at a time, and afterwards, they journal their feelings around their use of the computer.

They become members of GameQuitters.com (Cam Adair’s membership website for gamers and their families). And importantly, they clean up their computers so that they’re not getting ads for video games on You Tube etc.

We recommend that clients never again have a computer in their bedroom. Their computer should be in a common area in the house. We also recommend that they get an old-fashioned ‘brick’ phone instead of a smart phone.

So our whole approach is to re-train clients so they can control technology, rather than it controlling them.

We actually have clients who are practising this now, who graduated our programme when it first started a year ago. One client is studying and has a place at Uni.

And other features of the programme are the same as for those with other addictions?

Yes – we have process groups, we do a lot of CBT (very effective for depression) wilderness therapy and social responsibility. We visit and volunteer at the local orphanage. We clean up rubbish in the neighbourhood. The clients learn how to cook.

We have an ethos of ‘continuing care’ after a client has completed their programme (in which they built solid foundations). This is geared towards them having a meaningful and purposeful life. Continuing care is designed to build connection – because addiction is a disease of loneliness and isolation. It’s no good just stopping gaming (or stopping using drugs). The addiction needs to be replaced by something with meaning and purpose.

To help our clients find meaning and purpose when they move on from here and engage with life again, we ask them to focus on what they want to do with their lives. We ask them: “What is your dream and what makes you unique?” We aim to plant a seed in their minds.

It’s also important that clients have counselling lined up in the place they are going back to.

And as I mentioned earlier, we also ensure that our gaming addiction clients become members of GameQuitters.com, so they can get ongoing support from the GQ community. Being in recovery from gaming – as with other addictions – is a lifelong project.

What do you do if someone hates sports?

We coax, persuade and cajole them into participating. We sit down with them and explain why we’re doing this. We start slowly with them and then build up to greater amounts of physical activity.

Just before the weekend of the overnight hike, the clients all tend to develop migraines, or other reasons for not going. But they have to go anyway. Then on Monday they all talk about how they bonded through this physical adventure, and how the guys who’ve been in the programme for longer were able to help the new guys. The ‘old hands’ tell us how incredible it was to be able to help someone.

Humans are social animals. Connection produces dopamine, because connection is necessary for our survival and always has been.

From my conversation with you John, I’m getting a picture of the magnitude of the challenge society faces in our relationship with screens, social media and technology. Can you:

a) Express this challenge in a nutshell?

b) Suggest some approaches for parents to be pro-active in encouraging a healthier use of technology?

a) In a nutshell, young people are only interacting through their screens and through text messaging. They don’t know what a land line is and they don’t want to talk to their families. We don’t see many kids playing outside, because they’re texting friends from their bedrooms. But it’s not just young people. In the book “The Big Disconnect: Protecting Childhood and Family Relationships in the Digital Age” (Catherine Steiner-Adair, 2013), the author says research showed that the majority of pre-teens (8-10 year olds), felt that their parents were inaccessible. So we all need to reassess how much time we spend in front of screens – particularly our use of phones.

b) So first and foremost, to be pro-active, parents need to monitor their own use of phones and technology and model healthy behaviour.

- Have a rule whereby phones are turned off during meals.

- Kids are starting to get hooked on screens at 6/7 years of age. Stop handing toddlers a smartphone to keep them quiet – it‘s wiring their neural pathways so they become hooked at a very young age.

- Don’t allow kids to have a computer in their bedroom.

- Schools need to revert to using less electronics. (Steve Jobs didn’t allow his kids to use Ipads. He knew how addictive they were).

- The bullying that occurs on social media, responsible for so much teenage unhappiness and depression, needs to be addressed in schools. (All social media is designed to be addictive).

How optimistic are you that as a society, we can move towards a healthier use of technology?

We need to look at it in perspective. Once upon a time, the more educated people in society worried about what would happen if ‘the common people’ learnt to read.

Humans are wonderful at self-correcting. It’s a case of us all being aware of the challenge, combined with initiatives in schools. But it is vital that parents take responsibility themselves.

——————————————————————–

The Edge Rehab (part of the internationally recognised Cabin Group addiction treatment provider) is for young men between 18-26 years old. It is located in the jungles of northern Thailand, surrounded by mountains, rocky cliffs and waterfalls.

There are facilities for 120 clients, divided between four villages. www.theedgerehab.com

John Logan , Head Counsellor at The Edge, combines motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness and the 12-Step model of addiction recovery. He has worked as a member of multi-disciplinary treatment teams in both residential and outpatient settings with complex patients and diverse populations.

He has been involved in sport from a young age, was an accomplished amateur boxer and eventually went on to coach young men in this sport for several years. In later years he studied both Karate and Aikido.

John holds a BS and has worked as a counsellor in the Netherlands with the Dutch Addiction Treatment Foundation under the auspices of an accredited US and UK accredited trainer. He delivered substance abuse education in the largest addiction treatment centre in the Netherlands. As well as a counselling qualification, John has also completed courses in psychology with Trinity College Dublin and studied insight meditation for two years in the Dublin Buddhist Centre.

He has been working as an addictions counsellor in Thailand since 2013.

Cam Adair is the founder of www.GameQuitters.com (His interview with Letting the Light in can be found here: Gaming Addiction Interview with Cam Adair ).